(Photo from Shutterstock)

- Public-to-public transfers, sometimes called open enrollment or portability, are not robustly used. The policy is not a panacea. It can be a lifeline for hardship, though.

Forty-six (46) states, plus the District of Columbia, allow a student to transfer from the public school they are assigned to into another public school. Mississippi is among them.

Twenty-one (21) states allow these transfers to occur without the permission of the school the child is attempting to leave. Those states removed the ability of the child’s assigned school to hold him hostage or have “veto power.” The school the child wants to attend still has to say “yes.”

Under current Mississippi law, both the school the child wants to leave (“sending school”) and the school the child wants to attend (“receiving school”) must agree.

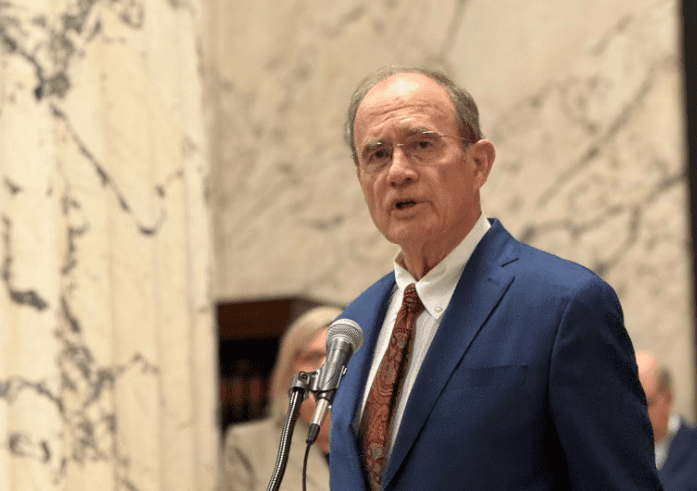

Both the House and Senate have proposed to become the 22nd state where a sending school lacks veto power — the House in its omnibus package and the Senate in stand alone fashion.

Nothing in either bill takes away a receiving school’s ability to say “we can’t accept this child.” The receiving school maintains autonomy.

That’s it. That’s the nothing burger change that has Xanax-popping Karens and Karls online freaking the heck out about “property values” and “culture” or whatever other euphemism they can come up with for “a Black kid might move into our suburban district.”

We don’t have to guess the impact. The twenty-plus states that do not permit a sending school a veto when the receiving school wants the kid answer the hysteria. Property values don’t plummet. Culture doesn’t crumble. A black market for student athletes does not rise up.

There’s not a mass exodus of students or an “invasion.” Good schools continue to be good schools. Johnny and Jamal get along just fine.

What does happen is that a kid who happens to live close to a district line can attend a school that’s actually closer to where she lives. A parent who struggles with transportation, or after school care, can place their child closer to where they work or to a relative who can provide a soft spot to land until mom gets off from her job. A kid who is getting bullied can find a new beginning.

Public-to-public transfers, sometimes called open enrollment or portability, are not robustly used. The policy is not a panacea. It can be a lifeline for hardship, though.

One group of people who understand this well are teachers. Mississippi law presently creates an exception that allows teachers to have their own children attend the school where they teach. In addition to that, some districts in the state have policies that allow teachers to place their own children anywhere within the district — not just in the school they are assigned to or the school where the teachers works.

This was recently described to me as a “perk of the job.” Perks are benefits. The word means it’s something positive. Good for the parent. Good for the child. And I agree. It’s great the state and some districts afford teachers this latitude. It’s an opportunity all parents — the people paying the taxes that fund the schools — should have.