- The summer of 1964 was a major turning point in the Civil Rights Movement, demonstrating the power of ground-level activism and interracial cooperation.

People often take many rights in today’s society for granted, such as the right to vote. Anyone over 18 in Mississippi can register to vote, and as long as they have a valid ID, they can head to the voting precinct on election day and cast their vote.

But there was a time in the not-too-distant past when African American Mississippians didn’t have the legal right to vote. When they were granted that right, the lack of knowledge on how to engage, coupled with the fear of violent retaliation and job loss, paved a barrier between Black Mississippi and the ballot box.

Freedom Summer was born from a collection of African American civil rights agencies that united to stand strong against this systemic oppression. The state was flooded with volunteers, movers, and shakers in the Civil Rights Movement to get more African Americans registered to vote and educated about why they should be engaged in their local politics.

The force behind Freedom Summer

In the early 1960s, the Southern United States was a hot spot of racial discrimination. Even though the 15th Amendment granted the right to vote, African Americans in the South, including Mississippi, faced formidable barriers, including literacy tests, poll taxes, and outright intimidation. By 1962, less than 7% of eligible Black voters were registered in Mississippi.

“Freedom Summer was a project under the umbrella of COFO, the Council of Federated Organizations,” said Micheal Morris, Executive Director of the Civil Rights Museum at the Two Museums in Jackson, Mississippi. “Under the COFO ‘umbrella’ were other civil rights organizations, such as the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), people in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).”

Hundreds of volunteers flooded Mississippi, from Greenwood to Hattiesburg and beyond, to bulldoze the barriers preventing the Black vote from occurring in Mississippi. Fannie Lou Hamer, Robert Moses, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. were pivotal in tackling systemic oppression head-on in the Freedom Summer movement. Medgar Evers was also part of the groundwork that had been laid for Freedom Summer, though he was assassinated the year before.

Tackling the Issue

Freedom Summer had three primary goals.

“The first was registering African Americans to vote across the state,” said Morris. “In 1963, less than 6% of African Americans in Mississippi were registered to vote.”

The second goal of the movement was the establishment of Freedom Schools.

“They created Freedom Schools throughout Mississippi, which was an idea of an SNCC worker named Charlie Cobb,” said Morris.

According to Morris, the third objective of Freedom Summer became the driving factor.

“The main goal became to challenge the state Democratic Party at the Democratic National Convention,” said Morris. “And to do that, you had all of the voter registration and education going into the summer, and Fannie Lou Hamer addressing the Democratic National Convention’s Credential Committee that August.”

This was done by creating the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which Hamer represented when she spoke at the DNC in August 1964.

Hamer held nothing back in her address to the committee at the convention. After outlining the dangers she faced, from losing her job to being imprisoned to having the home she was staying in shot at 15 times in a drive-by shooting by racists, Hamer had a challenge for the committee.

“All of this is on account we want to register, to become first-class citizens, and if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America, is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave where we have to sleep with our telephones off of the hooks because our lives be threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

Voter Registration Drives

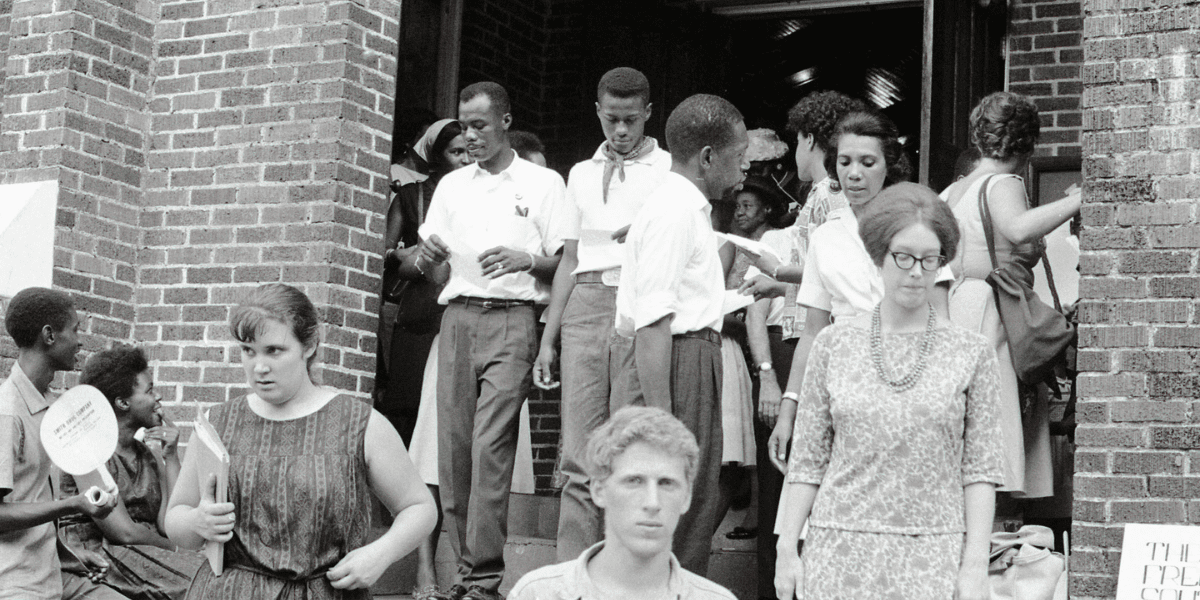

One of the major components of Freedom Summer was the voter registration drive. Hundreds of volunteers, many white college students from the North, traveled to Mississippi to assist African Americans in registering to vote.

White supremacist groups and even local authorities did not respond well to the drive, threatening and carrying out violent attacks against the volunteers and the participants and striving to strike fear and intimidation to anyone pushing for more African American civic engagement.

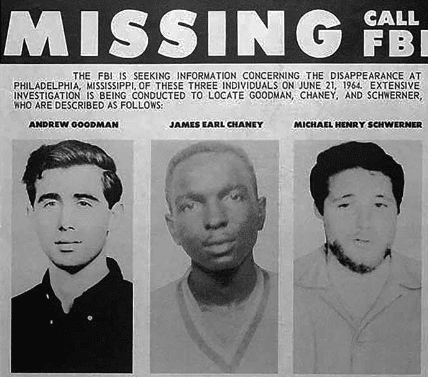

The disappearance and subsequent murder of three civil rights workers, Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner, on June 21, 1964, underscored the lethal dangers faced by those involved in the movement. The men disappeared while investigating a church burning in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

June 21st marks the anniversary of when Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney went missing. Their bodies were found in August.

Their disappearance was on the minds of other Freedom Summer volunteers throughout that summer.

Despite all the risks, the voter registration drives made significant strides. The initiative not only increased the number of registered African American voters but also highlighted the severe injustices of the Jim Crow South, drawing national attention and eliciting widespread support for the civil rights cause.

Freedom Schools

Another cornerstone of Freedom Summer was the establishment of Freedom Schools. These schools aimed to provide African American children and adults with a quality education that was otherwise inaccessible due to the racially segregated and underfunded public school system in Mississippi. The curriculum promoted critical thinking, cultural awareness, and political activism. It included African American history, civics, constitutional rights, and basic literacy and math skills.

“This was an alternative to the little bit of education African Americans had if they had any. They taught African American history, taught them about their heritage, and taught them to be proud of who they are and develop a sense of pride,” said Morris.

The Freedom Schools also served as safe spaces where students could discuss the social and political issues affecting their lives. The educational initiative improved literacy and academic skills and instilled a sense of empowerment and community among participants. Many students from Freedom Schools went on to become active leaders in the civil rights movement.

Community Centers and Churches for solace

Freedom Summer also saw the creation of community centers, which provided a range of services to African American communities. These centers offered legal and medical assistance, literacy classes, and recreational activities. They became focal points for organizing and mobilizing residents, fostering a sense of solidarity and collective action. The community centers played a critical role in sustaining the momentum of the civil rights movement at the grassroots level.

Even before Freedom Summer, many local churches became safe havens for those dedicated to racial equality.

“Freedom Summer volunteers found solace and protection in these churches. And many of the movement leaders, the local leaders in these communities, operated out of the church,” said Morris.

“The church was an important place because it was independent of the white power structure in the state. When you research the Civil Rights Movement leadership, you see a lot about this notion of mass meetings,” said Morris. “If I had to compare it to anything, they were like church services. Church services would be circled around this idea of voter participation and civic engagement.”

During breaks in the singing and scriptural-based portions of the meeting, speakers like Medgar Evers would take to the pulpit.

“There are recordings of him (Evers) speaking in Greenwood, Mississippi, and he sounds a lot like a preacher,” said Morris. “His message is the importance of being involved and engaged in the political process, and so it was these mass meetings where they’re encouraging African Americans to overcome fear and go down to the courthouse and get registered to vote.”

Rising above the threats, changing the future

Freedom Summer was not without its challenges. The volunteers and activists faced intense opposition from local white supremacists and law enforcement. Violence, intimidation, and arson were common tactics used to undermine the movement. The federal government, while supportive in rhetoric, was often slow to provide the necessary protection and intervention.

Fannie Lou Hamer of Ruleville, Mississippi, outlined some of the dangers she faced in her speech to the DNC committee in August 1964.

“Hamer went down to the courthouse to register to vote in 1963,” said Morris. “She was a sharecropper working on a plantation, and the plantation owner kicked her off the property, along with her family. So she was homeless and had no job.”

Hamer also discussed the threats she faced aside from her job loss. She recalled an instance of being arrested and beaten after attending a voter registration workshop in June 1963, a year before Freedom Summer:

“And it wasn’t too long before three white men came to my cell. One of these men was a State Highway Patrolman and he asked me where I was from, and I told him Ruleville, he said, “We are going to check this.” And they left my cell and it wasn’t too long before they came back. He said, “You are from Ruleville all right,” and he used a curse word, and he said, “We are going to make you wish you was dead.”

I was carried out of that cell into another cell where they had two Negro prisoners. The State Highway Patrolmen ordered the first Negro to take the blackjack. The first Negro prisoner ordered me, by orders from the State Highway Patrolman for me, to lay down on a bunk bed on my face, and I laid on my face. The first Negro began to beat, and I was beat by the first Negro until he was exhausted, and I was holding my hands behind me at that time on my left side because I suffered from polio when I was six years old. After the first Negro had beat until he was exhausted the State Highway Patrolman ordered the second Negro to take the blackjack.

The second Negro began to beat and I began to work my feet, and the State Highway Patrolman ordered the first Negro who had beat to sit on my feet to keep me from working my feet. I began to scream and one white man got up and began to beat me on my head and told me to hush. One white man—my dress had worked up high, he walked over and pulled my dress down—and he pulled my dress back, back up.”

Though dangers and challenges were numerous, the movement prevailed. Thanks to Freedom Summer, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, which meant that American citizens had the right to vote no matter their skin color, and discrimination against such is illegal.

The legacy of Freedom Summer endures. It was a major turning point in the Civil Rights Movement, demonstrating the power of ground-level activism and interracial cooperation. The campaign registered thousands of African American voters and forged national support for civil rights and racial equality.

Freedom Schools’ educational initiatives have had a lasting impact and inspired a culture that appreciates African American legacy and heritage while educating about Black history.

Freedom Summer was a massive effort that transformed America’s civil rights landscape. The combination of voter registration, education, and community empowerment challenged the systemic racism in the state and around the Deep South and inspired a generation of activists.

Honoring Freedom Summer today

Though Freedom Summer was 60 years ago, the sacrifice of the volunteers and participants cannot be overlooked. And though 60 years ago is not too distant in memory, generations today never experienced the pain that the volunteers and participants had to face.

So, how can you honor Freedom Summer today? By learning more about it.

The Mississippi Civil Rights Museum at Two Museums in Jackson has a gallery dedicated to Freedom Summer entitled “I Question America”, named after the iconic Fannie Lou Hamer speech to the DNC in August 1964. The emotionally moving gallery brings history to life by showing the reactions to the movement and its impact on the world.

There are also several events at the museum this summer to bring education and remembrance regarding Freedom Summer. Click here for more information about these events.