- With the 71st Jimmie Rodgers Festival on the way, Jim Beaugez takes a look back at its history and the legacy its namesake left behind.

When the 71st Jimmie Rodgers Festival kicks off May 12 in Meridian, the weeklong series of events in honor of the country music pioneer will hearken back to the early days of the Queen City’s signature event.

“People came from all over and would camp out in Meridian and would stay for the whole week,” says Leslie Lee, executive director of the Jimmie Rodgers Foundation, which produces the festival.

As the festival grew from its first concert in 1953, fans from around the world planned vacations to coincide with the festivities, using the opportunity to soak up the region’s hospitality and visit other music destinations like New Orleans and Memphis. Many of the same events festivalgoers enjoyed in those early years, such as the talent competition, are on the slate for May 12-19.

“The number one thing the Jimmie Rodgers Festival is known for is finding new talent and getting them out there first,” Lee says.

At the inaugural edition of the festival, which drew an audience of 50,000, an unknown singer named Elvis Presley competed in the talent contest and placed third. Two years later, he headlined the entire festival. Nearly two decades later, Garth Brooks played the main stage just weeks before his hit “Friends in Low Places” dropped and became one of country music’s most iconic songs.

The strongest thread running throughout the festival’s history, though, is seeing country music stars pay tribute to Rodgers, known as the father of country music for his role in creating the genre’s early works. Born in Meridian in 1897, Rodgers grew up the son of a railroad man and quit school in his teens to follow him into the trade. After a diagnosis of tuberculosis at age 27 sidelined his career, he began to focus seriously on the music he had performed on traveling shows while still a schoolkid.

Rodgers made his first recordings three years later in Bristol, Tenn., at the historic August 1927 Victor sessions that also included the Carter Family. While his initial single was a modest success, a song recorded at another session that November made him a star — “T for Texas,” released as “Blue Yodel,” which sold half a million copies. He enjoyed fame until his untimely death in 1933 from complications of tuberculosis.

The music Rodgers performed and recorded during those final six years of his life influenced an untold number of musicians, though. By the early fifties, future Country Music Hall of Famers Ernest Tubb and Hank Snow began organizing the first festival to honor Rodgers in his hometown.

A 14-year-old Ken Rainey rode his bicycle from the south side of Meridian to Ray Stadium for that first concert. With a lineup headlined by Tubb and Snow, the show was produced revue style akin to the Grand Ole Opry, with a rotating cast of artists.

“You name them, the people were here,” says Rainey. “I mean, senators and congressmen and governors were here, and when the show started, it was just one person right after the other. They would do maybe one or two songs, and the next one would come on. It was just phenomenal.”

After a successful run, the festival eventually petered out. But after Rainey became a WOKK-FM radio disc jockey, he and two friends and colleagues, Carl Fitzgerald and James Skelton, saw the potential in rebooting the event and began to reorganize the festival. By 1972, the Jimmie Rodgers Festival was back — but whereas Tubb and Snow attracted star power, Rainey and his cohorts had few resources other than persistence.

Rainey began pursuing artists to stop in between shows to play the festival, including Merle Haggard, who in 1969 had released a tribute album to Rodgers, Same Train, A Different Time: Merle Haggard Sings the Great Songs of Jimmie Rodgers. Whenever Haggard played in Jackson, Rainey would slip promotional literature about the festival onto his tour bus while the band played.

“I did this for about seven or eight years, and I get this call one night about 10 o’clock, and the guy said, ‘Are you the guy who’s been putting that junk on our bus about Jimmie Rodgers?’ I said, ‘Well, depends on who you are.’” He happened to be Tex Whitson, Haggard’s manager, and was calling to tell Rainey to cut it out. But Rainey turned it around with a dose of gumption. “I said, ‘Why don’t you come on down here and do this show and I won’t have to do it anymore.’”

The festival didn’t get Haggard that year, but after Whitson visited Meridian and saw the concert was truly a charity event, the two became friends. Haggard went on to play four editions of the festival in the late seventies and eighties. During the next three decades, country music stars like Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Randy Travis and others played the festival. After another short break, the event roared back in the 2010s with artists like Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit, Chapel Hart, and Christone “Kingfish” Ingram.

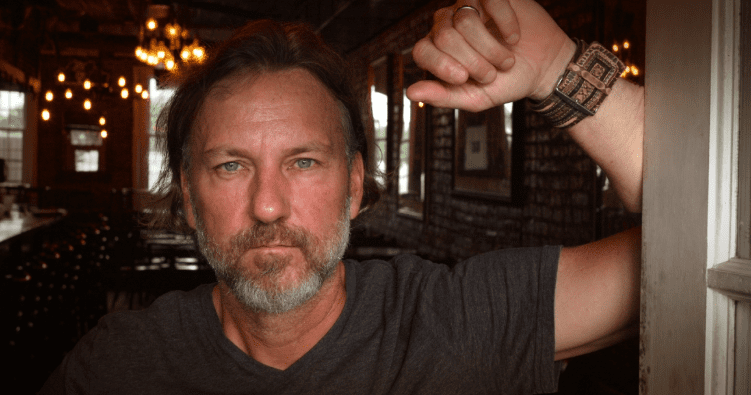

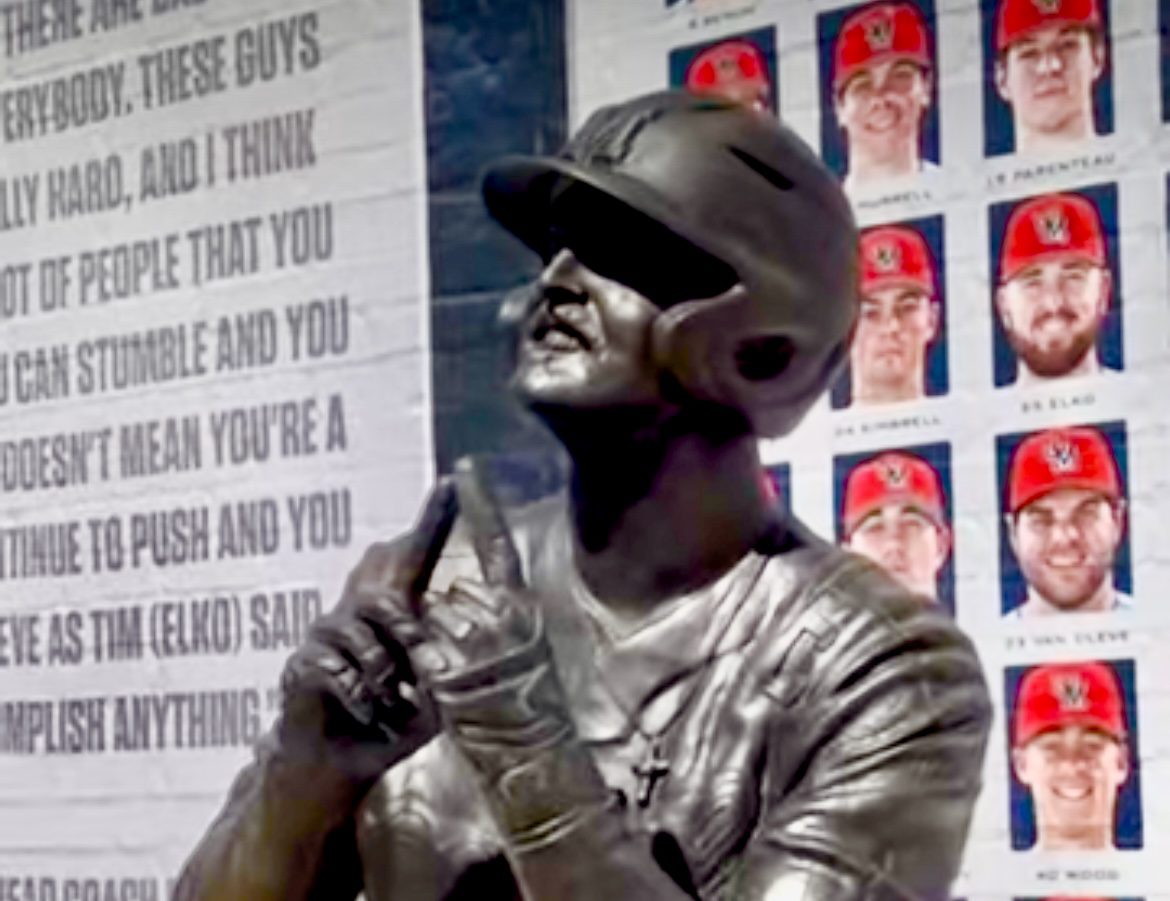

This year, official Jimmie Rodgers Festival concerts will feature Ben Haggard, Merle’s son, as well as the Red Clay Strays and Trey Lewis, along with festival traditions like the talent show, a music history night and Sunday gospel brunch. For Meridian, whose downtown now boasts a multi-story mural of Rodgers in his famous thumbs-up pose, pride in their native son runs deep.

“I like to think of Jimmie Rodgers’s legacy as a gift that Meridian has to give to the world,” says Lee. “We’re the Queen City and he’s the top jewel in our crown.”