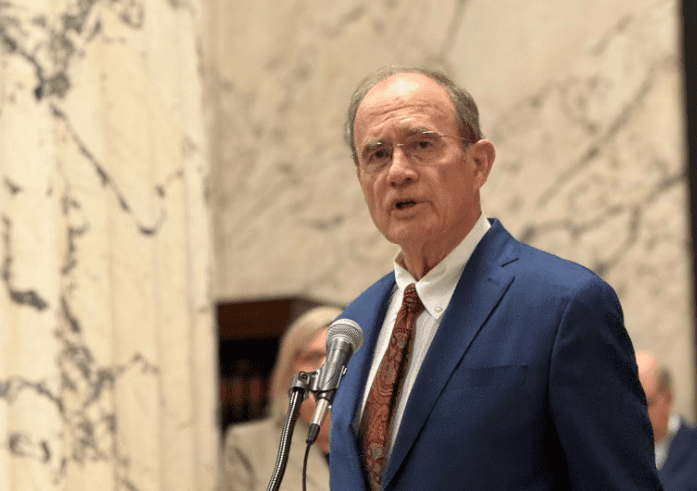

Republican presidential candidate and former Vice President Mike Pence speaks about his book, "So Help Me God," Saturday, Aug. 19, 2023, at the Mississippi Book Festival in Jackson, Miss. Pence was one of several dozen authors who participated in a variety of panels or sit-down interviews for festival attendees. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

- Under then-Gov. Mike Pence, Indiana was one of the first states to expand Medicaid following the passage of Obamacare. It now faces a billion dollar shortfall in the program and is slashing benefits to disabled families.

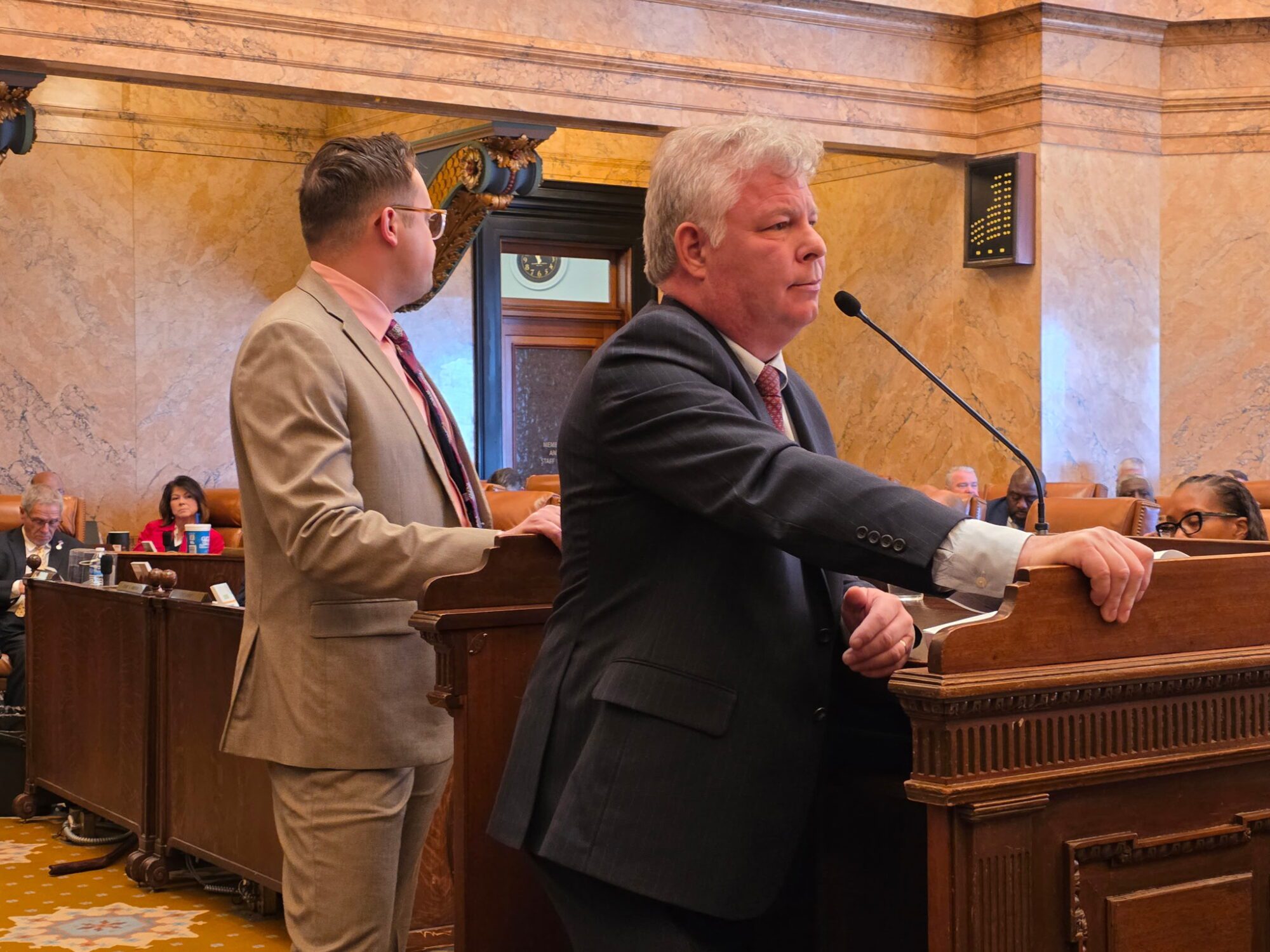

A few weeks ago, Division of Medicaid Executive Director Drew Snyder testified in the Legislature that state funding for Medicaid would need to increase by over $500 million in the next two years to keep pace with the cost of the existing program — before expansion.

Over the weekend, Jonathan Bechtle wrote in The Wall Street Journal about Indiana’s own Medicaid cost overruns as the state begins slashing benefits to make up for a billion dollar budget shortfall:

“The bill for ObamaCare’s Medicaid expansion is coming due. Nine years after Indiana became one of the first Republican-led states to sign up, the fiscal pain has become too much to bear. Yet in the rush to save taxpayers, Indiana is moving to cut funding for Medicaid’s neediest beneficiaries rather than the able-bodied adults covered by expansion.

Late last year, Indiana announced that its Medicaid program faced a roughly $1 billion shortfall or, as officials called it, a “forecasting error.” While the state is blaming cost overruns on traditional Medicaid, the 2015 expansion by then-Gov. Mike Pence is wildly over budget, too. It cost taxpayers nearly $5.4 billion in 2023 alone, with roughly $540 million paid for by Hoosiers. This is the inevitable result of Medicaid expansion, which has enrolled far more people than advocates predicted.

In 2015 Indiana estimated that roughly 433,000 would join the Healthy Indiana Plan, as the state’s Medicaid expansion is called, in its first two years. Officials predicted enrollment growth would remain stable after three years. But by 2023 enrollment reached 604,000—40% more than anticipated. Taxpayers are covering a new class of able-bodied adults who should be pursuing work to pay for health insurance. Instead, Medicaid expansion encourages them to work less, or not at all, to get the taxpayer’s help.

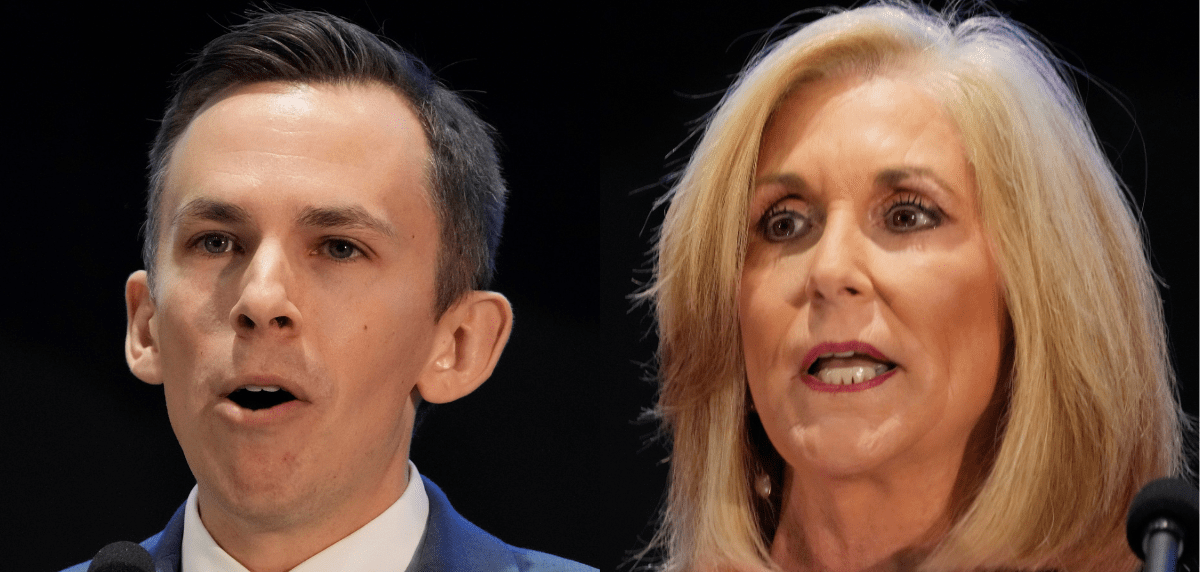

The $1 billion budget “error” is bad enough, but the state agency’s response was even more shocking. In January the Family and Social Services Administration announced plans to cut payments to caretakers—usually parents or spouses—of elderly and disabled Hoosiers. The blowback was swift, with parents protesting outside the statehouse. They have a point: Indiana is cutting funding for families of children with severe disabilities.”

Medicaid was originally designed as part of the nation’s welfare safety net to provide health insurance to the most vulnerable populations in the country — children, pregnant moms, the disabled, elderly, and caretakers. Bechtle explained that the reason Indiana was cutting benefits first for disabled families, instead of the able-bodied adults made eligible for Medicaid under Obamacare, has to do with the funding structure for Medicaid expansion:

“Hoosiers can be forgiven for wondering why Indiana isn’t targeting able-bodied adults in the Medicaid expansion population. Surely it makes more sense to cut funding for people who are far more able to find private coverage. But good sense and Medicaid expansion don’t mesh. Its design ensures that truly vulnerable people will lose Medicaid funding first.

At the heart of Medicaid expansion is a perverse incentive. The federal government has agreed to pay 90% of its costs, yet for traditional Medicaid it pays a little under 65%. For the people who run Indiana’s budget, there’s only one logical solution for closing the budget shortfall: cut funding for people who only bring in 65 cents on the dollar, instead of those who bring in 90 cents. It doesn’t matter that the 90-cent group includes those who are able-bodied and could receive health insurance elsewhere. Washington is footing more of the bill, and states have an incentive to keep it that way.”

Finally Bechtle highlighted Medicaid expansion cost overruns and the very real risk that the federal government reduces its share of the cost for the Medicaid expansion population:

“The per person cost to taxpayers is at least 64% higher than predicted [for the expansion population], meaning every expansion state is on the same dismal road as Indiana. When the budget shortfalls arrive, more states will cut funding for disabled children along with elderly and impoverished Medicaid recipients, while leaving able-bodied adults on Medicaid expansion untouched.

The only way to flip the script is for Congress to slash its 90% payment rate for Medicaid expansion. That’s increasingly likely amid soaring national debt and deficits, and the Congressional Budget Office is already gaming out the potential effects on the federal budget. But if—or rather when—that happens, states will find themselves in an even bigger fiscal bind, paying far more for able-bodied adults in the expansion population. To stay in the black, they’ll have to make deep cuts.”

If Mississippi expands Medicaid and then Congress reduces the percentage the federal government pays, it would result in massive budget holes that could only be covered by increasing taxes and cutting funding for important government functions like education.