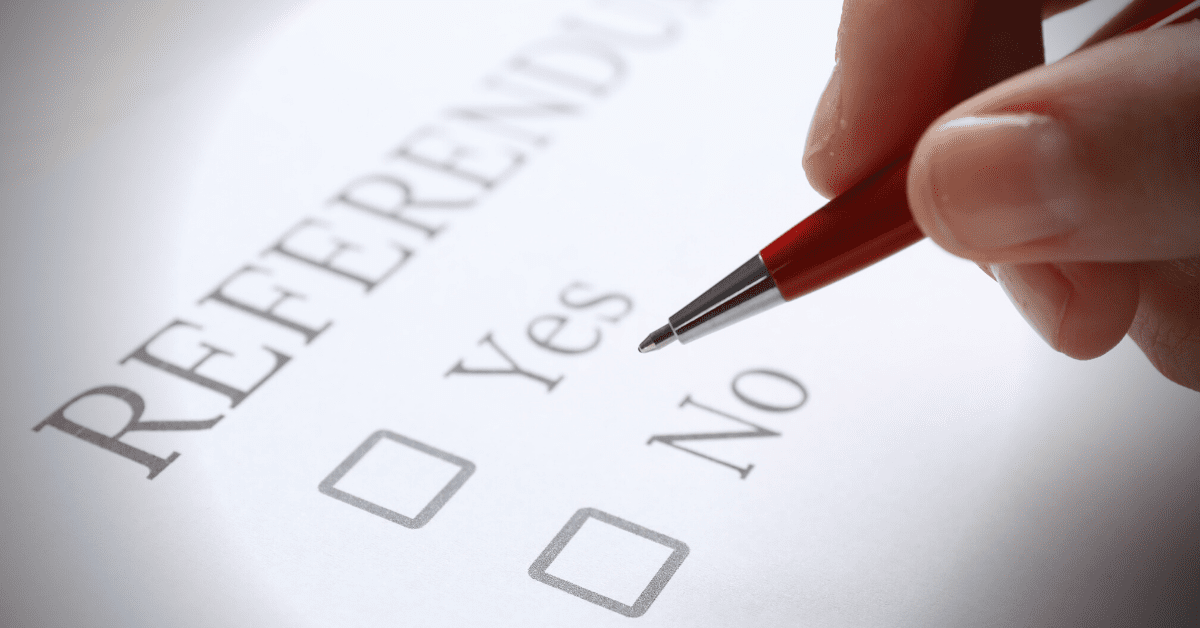

Clearly, there is an appetite for “citizen intervention” among state voters.

Statewide elections will be on the ballot later this year for all state eight statewide executive branch offices, all state district offices and for all 174 posts in the Mississippi Legislature in addition to county offices and county district offices in all 82 Mississippi counties including district and county attorneys.

What won’t be on the ballot this year – or in the years to come until the Mississippi Legislature takes action to correct flaws in the state’s existing “direct democracy” statute – will be voter-driven ballot initiatives.

But make no mistake, during the last courthouse-to-statehouse round of elections in 2019, Mississippi voters had a legal vehicle to put issues on a statewide referendum ballot that no longer exists. Why? It’s a long political story.

In the 2020 elections, Mississippi voters approved a voter initiative authorizing a medical marijuana program outlined in Initiative 65 over the express objections of the majority of legislative leaders. Mississippi voters gave Initiative 65 their 73.7% approval while giving the legislative alternative Initiative 65A only 26.3% of the vote.

The pro-medical marijuana initiative outpolled Republican incumbent President Donald Trump by some 20 percentage points with state voters — even outpolling the state’s 72.98% decision to change the state flag.

But the results of that referendum were annulled by the Mississippi Supreme Court. The state’s High Court ruled that the state’s 1992 ballot initiative process was flawed because the Legislature had spent several years without addressing the impact of Mississippi’s loss of a congressional district in 2001 on the constitutional provision governing that process.

The court ruled that the state’s initiative process was broken and that because Initiative 65 was put in motion through that flawed process and procedures, the medical marijuana initiative could not stand despite overwhelming voter support.

In 2022, the Legislature and Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves essentially negotiated a medical marijuana statute that was smaller and tighter in scope than the ballot initiative, but that at least got the issue off-center for many patients who believed they needed the drug.

There has existed a sort of iron triangle between the voters, the Mississippi Legislature, and the state Supreme Court for more than a century on the issue of ballot initiatives. The voters have struggled to hold on to their ability to bypass the Legislature in changing public policy in the state.

Why? Because the Legislature designed the former initiative process in Mississippi to be difficult for those who wish to circumvent lawmakers and get into the business of directly writing or changing laws for themselves. The state’s high court has vacillated over the years on their interpretations of direct democracy in the state.

Since 1993, there have been 66 instances where various Mississippi citizens or groups have attempted to utilize the state’s initiative process. Some 52 of those attempts simply expired for lack of certified signatures or other procedural deficiencies.

In the fallout from the Supreme Court’s decision to throw out the political result of Initiative 65, it became clear that many lawmakers were prepared to shift the ballot initiative process away from constitutional changes as allowed by the 1991 initiative process to a process that will enable statutory changes only.

But even if lawmakers do what’s necessary to enable statutory ballot initiatives, state voters will have far less power than they had before. There is a fundamental difference between being able to change the state’s constitution and changing a statute.

Some 26 states have the right to ballot initiative or referendum processes, excluding most Southern states except Florida. If Mississippi can reclaim the right of ballot initiative, even if for statutes only, it will represent a victory of sorts compared to most of our neighboring states.

There is a legislative deadline for action this week to change the state’s ballot initiative process. Failure to restore – or at least partially restore – those rights to Mississippi voters will likely result in a lot of uncomfortable questions from voters to incumbents on the campaign trail.

Clearly, there is an appetite for “citizen intervention” among state voters. Just as clearly, there is also concern among those in political power about a full restoration of the 1991 Mississippi initiative process. Those concerns link back to Initiatives 42 and 65 – and extend forward to what state voters would do with a Medicaid expansion referendum.