- Revels fought for equality early and often in his short tenure in the United States Senate, but did so from a position of mercy and grace.

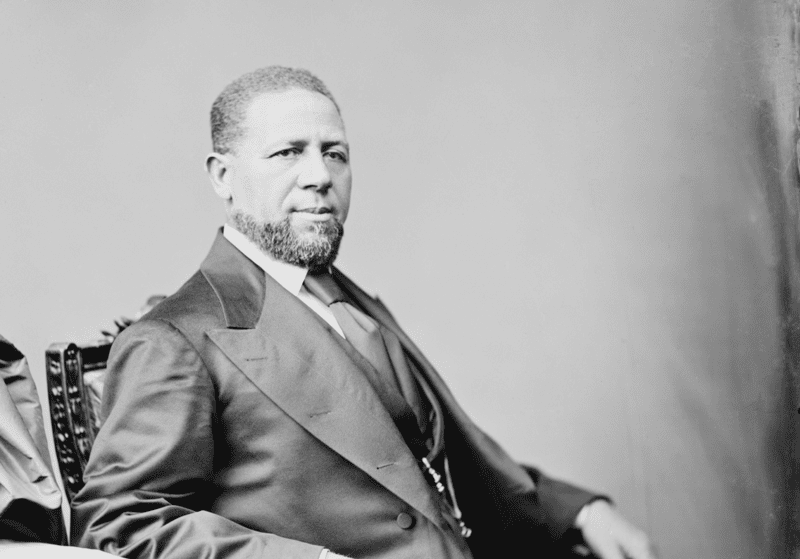

Hiram Rhodes Revels is most commonly known as the first Black man to serve in the United States Congress. Revels was selected to serve in the U.S. Senate by the Mississippi Legislature in 1870, during the Reconstruction Era.

At the close of the Civil War, Congress enacted a series of laws that put southern confederate states under military control for purposes of reconstituting state governments. These newly formed governments excluded former confederate soldiers from participating politically and were filled with Republicans loyal to the Union (see Editor’s note).

The Republican Party in the South at the time was comprised of a coalition of Black citizens empowered with the right to vote, northerners who settled in the South following the Civil War (derisively called “carpetbaggers” by some white natives), and a smattering of native white Republicans (again derisively referred to as “scalawags”). The governments formed saw African American leaders elected across the South. During this period, which lasted until 1877, 16 African Americans would serve in Congress. More than 600 were elected to state legislatures. Over 1,000 more held local offices.

But Revels was the very first sent to Congress and one of only two Black men who would serve in the Senate during this period in history — the other being Blanche K. Bruce, who also represented Mississippi. (Bruce, who moved to Mississippi in 1868, was elected in 1874 and served a full term in the U.S. Senate).

Revels lived all over the South throughout his childhood and as a young adult. Revels was born in Fayetteville, North Carolina, September 27, 1827. The Revels family was a free family—they were not enslaved and hadn’t been since before the Revolutionary War.

When Revels was just eleven years old, he went to live with an older brother in Lincolnton, North Carolina, where he studied to be a barber in his brother’s shop. Three years later, his brother died, and when his brother’s widowed wife was set to remarry, she transferred ownership of the barbershop to Revels.

Revels in Ministry and Military

From there, Revels felt a calling into Christian ministry. After attending seminary in Indiana, Revels was ordained into pastorship within the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1845. As many pastors do, Revels answered the call to preach in many churches across the Midwest. He was actually imprisoned for preaching to Black people in Missouri in 1854. Following that imprisonment, Revels went back to school to study religion at Knox College in Illinois. After that, he moved to Baltimore, Maryland, where he pastored a church and serve as the principal for the local high school.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, just four years after Revels began preaching and educating in Baltimore, he joined the Union Army. He also organized two Black units for the Army and fought at the Battle of Vicksburg in 1863.

When the war ended in 1865, Revels left the AME church for the Methodist Episcopal Church. A year later, he was called to a permanent pastor position in Natchez, Mississippi. For the next few years, he took a state administration position within the Methodist Episcopal Church, founded schools for black children, and served as a city alderman.

Revels’ Road to Congress

Revels, who was fairly new to Natchez, was elected in 1868 by the Adams County community to serve in the Mississippi State Senate, after just one year of being an alderman.

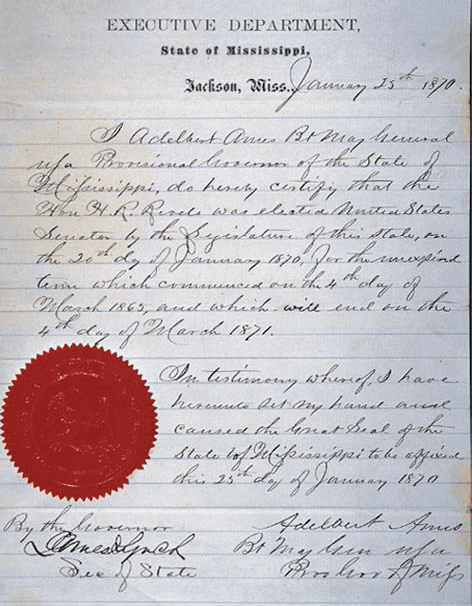

A condition of re-admission to the Union was state ratification of the 14th Amendment. Mississippi ratified the 14th Amendment on January 17, 1870. It was formally re-admitted on February 23, 1870, and on February 25th, after two days of debate, Revels was selected to fill the remainder of the term of a seat that had been vacant since the Civil War by the Mississippi Legislature. The final vote on his selection was 81 to 15. (Prior to the passage of the 17th Amendment in 1913, U.S. Senate seats were filled by state legislatures instead of by popular vote).

While his election by the Mississippi Legislature seemed to go smoothly, the fight for Revels’ seat was complicated by the United States Senate. In 1870, the Democrats in the Senate fought against Revels being seated. In the 1857 Dred Scott decision, the U.S. Supreme Court said that Blacks of African descent were not United States citizens. The Constitution requires that U.S. Senators be citizens for nine years prior to election. Revels opponents argued that at most he could be considered a citizen for four years, following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, but more likely only two years, following the ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868. The 14th Amendment gave citizenship status to anyone “born in the United States.”

Revels supporters argued that Dred Scott had been undone by the 14th Amendment and that there was nothing in the Amendment that prevented it from granting citizenship to people born in the United States prior to its ratification. They also argued that Dred Scott would not apply to Revels, even if intact, because Revels could trace a large part of his ancestry to Europeans, and thus, was not purely of African descent.

Over the objections, Revels was seated. He would serve only a single year (the remainder of the vacant term in the role).

The Fight for Equality

Revels fought for equality early and often in his short tenure in the United States Senate, but did so from a position of mercy and grace. While those on the more extreme end on his Republican side of the aisle wanted to continue to punish those who fought for the Confederate Army, Revels suggested reinstating their American citizenship with no more punishment, provided they vow loyalty to the United States.

Unfortunately, many of Revels’ attempts toward racial equality did not come to pass, at least not by his hand. Integration efforts he supported failed. A young Black man he vouched for in order to be admitted into the U.S. Military Academy was denied entry. Revels did, however, successfully campaign for Black workers to be employed at the Washington Navy Yard, as they were originally barred on account of their race.

After serving in the U.S. Senate, Revels returned to Mississippi. He became the first black president of Alcorn University, an HBCU in Claiborne County. While there, he also was elected to serve as Secretary of State in 1872. However, when he rallied against the re-election of then Governor Alderbert Ames, he was fired from Alcorn in 1874. In 1876, Ames was impeached, and Revels was reinstated at Alcorn until 1882, when he retired.

After retirement, Revels returned to full-time ministry and served at a Methodist Episcopalian church in Holly Springs, Mississippi. He also served at Shaw College, which is now Rust College. He died while attending a church conference in 1901 and is buried in Holly Springs at Hillcrest Cemetery.

The Mississippi State Legislature honored and forever memorialized H.R. Revels with a resolution in 2020. It read:

WHEREAS, it is the policy of the House of Representatives to appreciate our past so we can better define our future and to pay homage to an individual of Senator Revels’ caliber, who served as a trailblazing pioneer, and whose contributions merit honor and respect:

NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI,

That we do hereby celebrate the historic life and legacy of the Honorable Hiram Rhodes Revels as the first African American to serve in Congress as a United States Senator.

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED,

That copies of this resolution be furnished to the descendants of Hiram Rhodes Revels and to the members of the Capitol Press Corps.

Editor’s Note: There is a complex history surrounding political party identification and what is often referred to as party re-alignment. At the time of Revels’ service, Black Americans primarily identified with the Republican Party. Some historians have argued that the parties essentially flipped constituencies in the 1960s because of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — that African Americans became Democrats in response and white southerners became Republicans. The truth is more complicated. African Americans had begun voting Democratic well prior to the tumultuous period of the 1960s. Democrat Franklin Roosevelt won re-election with 71 percent of the African American vote, largely attributed to his handling of the Great Depression. But Democrats also controlled the “white South” with a majority of southern seats in Congress until the 1990s. In Mississippi, white Democrats held control of the state legislature and most state offices until the early 2000s. So while there has been racial realignment of party affiliation, it appears to have occurred more gradually and not around a single flashpoint in time.