- Trade deficits aren’t proof of bad trade deals, but of the wealth of the United States.

Standing in the Rose Garden last Wednesday, President Donald Trump held a poster purporting to show “tariffs charged to the U.S.A.” by country.

But the exorbitant rates reflected on the chart aren’t actually the tariff rates charged by any country.

Instead, the percentages were arrived at by dividing the trade deficit between the U.S. and each country, by imports from that country, times an elasticity multiplier (which happened to be wrong resulting in percentages four times higher than they should have been).

Countries with whom we have a trade surplus were still smacked with a 10 percent baseline tariff. This 10 percent baseline remains after a pause on the higher rates earlier this week.

It’s convoluted and not remotely reciprocal. Take Singapore. It charges a 0 percent tariff rate on U.S. exports. America has had a trade surplus with Singapore for 13 of last 14 years. But we’re still charging a 10 percent tariff on products domestic businesses import from Singapore.

What becomes apparent from these machinations is the administration’s focus was not on parity of rates, but on the elimination of trade deficits.

In determining whether that is the right goal — and whether it’s an achievable goal — consider these three questions:

- What is a trade deficit exactly?

- Who is the deficit really between?

- Who benefits and who loses?

Your Trade Deficit with Kroger

You have a trade deficit with Kroger. You buy more stuff from them than they buy from you. Kroger has not taken advantage of you. You voluntarily paid them for something you wanted, and which you were either unwilling or unable to produce yourself at a lower cost.

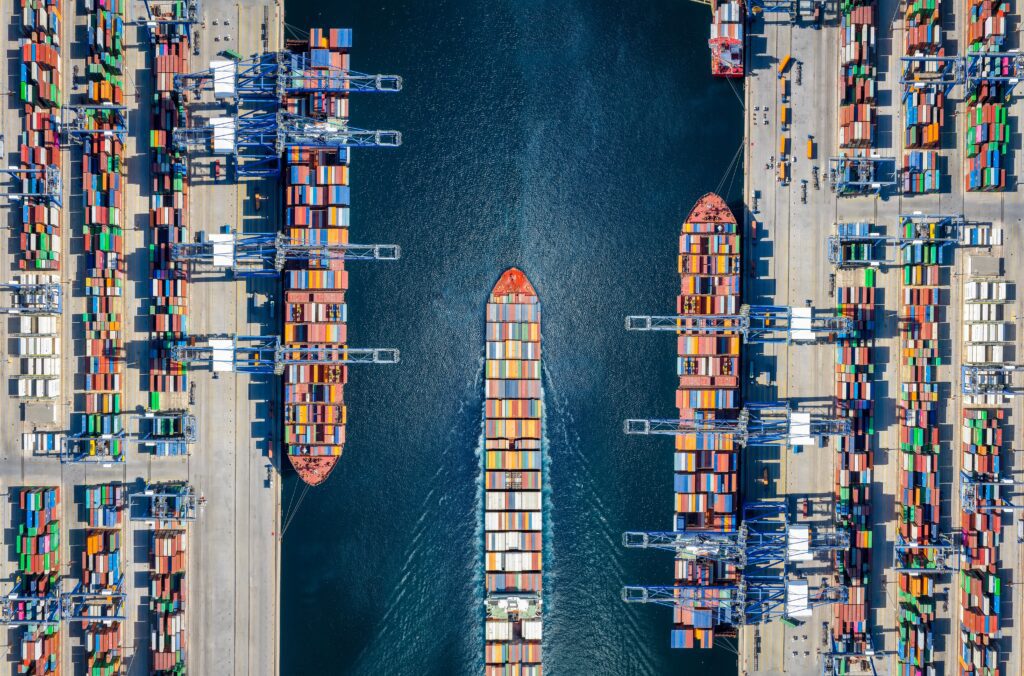

U.S. consumers and producers collectively have a trade deficit with consumers and producers from other countries. We buy more stuff from them than they buy from us.

This is due largely to the fact that we are a rich nation, with a strong dollar, and have more money to buy things. Frequently, poorer nations can produce those things when we can’t, or alternatively, more cheaply. In other words, we perceive what we are voluntarily buying as better deals.

We will never have a trade surplus with a country that has workers making $5 a day because they don’t have the money to buy our stuff back, which is expensive by comparison to the stuff they produce.

That is, unless we become very poor. During the Great Depression, the U.S. had a trade surplus of 19%.

The U.S. per capita GDP is now over $82,000. In Vietnam, one of our largest trading partners for clothes and consumer goods, the per capita GDP is just over $4,000. People in Vietnam aren’t missing out on Ford F-150s because of Vietnamese trade restrictions, but because they can’t afford an $80,000 truck.

Who is the Deficit Between?

There is increasingly a mental model in conversations around trade and tariffs that sovereign countries are doing business with each other.

But when Joe in Canton buys a Sony television at Wal-Mart, that’s not the United States doing business with Japan. The transactions are between a consumer and a retailer, and a retailer and a manufacturer, who happens to be located in Japan.

Similarly, when Wal-Mart imports televisions from Sony, it is not the nation of Japan that must write a check for tariffs charged by the United States. Wal-Mart writes the check.

Then the loss gets eaten, up and down the supply and distribution chain, ending with the consumer. Roughly 95% of tariffs are paid for by domestic importers and their customers. If consumers bore the full brunt of the increases, the Yale Budget Lab estimates it would add $4,700 in new expenses onto the average American family.

It’s important to note that even when companies don’t pass the full cost on to customers, there is a consequence. It looks like reductions in capital expenditures, hiring or investor profits.

This is why Wall Street is predicting companies won’t be as profitable if the tariff regime hangs around. Higher costs, lower demand. It’s also why the market spikes at the hint this may come to an end.

We will never be able to onshore the manufacturing of cheap consumer goods without making those goods very expensive. There are 600,000 manufacturing jobs in the U.S. today. The lines of people waiting to make tupperware, stuff teddy bears, and sew tennis shoes isn’t long.

We do export an awful lot, though. More goods than everyone but China, and more services than anyone in the world. Our largest businesses also have global locations, extracting immense wealth from those places and onshoring it stateside.

Who Wins, Who Loses

When you shop at Kroger (or any other grocery store), the first impulse isn’t “man, I’m getting ripped off.” For most, it’s “man, these avocados from Mexico will go great with some chips,” “these bananas from Costa Rica will make for some nice pudding,” or “this coffee from Colombia gives me some pep in the morning.”

That’s because you see the value in having the thing you are using your money to buy. It’s important to remember that money, itself, is not the end. It’s an instrument that allows you to acquire the things you need or want.

So when you spend money on an item imported from overseas, you’ve not been robbed. You’ve acquired something you find valuable.

Maybe your trade deficit with Kroger isn’t that bad.