- The debate over anti-poverty programs has never been between really good people, who want to help the poor, and really bad people, who want to see the poor suffer. The debate really should be about what set of principles and ideas offers the greatest opportunity to escape generational poverty and live a life of meaning and contribution.

On a steamy July day in 1981, I emerged into the world. My dad was off in California living a 1960s dream of becoming a musician. My mom had dropped out of high school and married him at 16. She’d had my oldest sister at 18 and our middle sister a few years later. I was last.

My mom labored for three long days in a charity hospital in Independence, Louisiana with me. It was arguably malpractice. The umbilical cord wrapped around my big noggin cut off oxygen (I know, the jokes write themselves). As a result, I was diagnosed with a “mild” case of cerebral palsy.

For a time period in my youth, I had a Forrest Gump-style brace on my left leg. That builds character in a PE class in the 1980s, back when coaches in polyester shorts had no problem calling kids ‘sissies’ and kids didn’t cry about it. Now people see the limp and just assume it’s an old injury. It never stopped me from doing anything, and I know that I am lucky having seen severe cerebral palsy cases.

When you’re a kid, you don’t know that you’re “poor.” Your normal is normal. But the older you get, memories start to stick out.

After living in a series of motels and relatives’ houses, our family built a little house in Hancock County. My dad, who had “sort of” given up his dream of being a Beatle, designed it and did most of the work himself. I’m not sure permits and building codes were a thing.

There was a single bathroom in the house accessed through my room. I recall moving in and it not having a bathtub or a toilet. We walked at night to a community swimming pool with shampoo and soap in tow. We would duck under water when car lights appeared because the pool was supposed to be closed after dark. To a 5-year old, it felt like an adventure. At home, the five gallon bucket that stood in place of the toilet felt less adventurous.

This period did not last long, but along the way, there were other signs. We had one car when most friends had two — a 1970s bright yellow LTD we kids affectionately called “the banana.” I remember people handing us money in church and thinking that was odd. I also recall lots of rice and gravy, and the occasional night of splitting a packet of Lipton soup with a can of tuna fish added for protein. I hated tuna, so it was a bummer.

It wasn’t always tight. My mom took a job at Wal-Mart when I was 6. She started as a cashier and worked her way up into back office management, eventually spending over 25 years with the company. I bristle to this day when people run down Wal-Mart, because it put food on the table and provided health insurance for our family. Sam Walton’s a hero in my book.

My dad worked construction. When he had a job, we had cable television and meat. When he didn’t, we didn’t. Our family moderated between low income and middle class.

My mom may not have finished high school, but whether in spite of, or because of, she poured into us the importance of education at an early age. I have fond memories of reading with her every night. I also have fond memories of my oldest sister, who quite fittingly became an educator, teaching me math that was well in advance of what we were learning in school. Those habits persisted.

She and I would go on to be the first members of our family to ever graduate college. Both of us were fortunate to receive academic scholarships, but even with the aid, and even working throughout college, I compiled a good chunk of student loans on room and board at Tulane, and later at Ole Miss Law.

When I graduated law school, I got another surprise. A family member had taken out a series of credit cards in my name and run up a considerable amount of debt. So for the first time in my life, I had a good paying job, at a good law firm, and was broke.

I rented a $400 month apartment in Jackson, returned to canned meat (chicken this time) and used every dime I made to pay off the credit cards, pay off an engagement ring for my wife, and save up for a rehearsal dinner and honeymoon. We upgraded to an $800 month rental when we were married, and drove old cars until the wheels fell off (my Mitsubishi Galant squealed so loudly when it started that the secretaries at my office made fun of me mercilessly). 60+ hour work weeks ensued. A habit that also persists.

In 2014, eight years into the practice of law and unsure of what I wanted to be when I grew up, I got a phone call that changed my trajectory. My middle sister had passed away unexpectedly. She was 36, with two young sons. I roused myself from bed, drove down to the Coast, picked up my oldest sister and then drove over to my mom’s house to tell her. That experience also leaves an impression. After making funeral arrangements the next day, I drove back to Jackson to pick up my family. I vividly remember having the thought during that drive that life was short and if I was going to do something that mattered, I better get on it.

So I quit the practice of law and started a chapter of a national think tank. And then after being in that world for 8 years, started a digital news outlet — at a time when media is dying on the vine. Both of those decisions probably led to some head scratching. Core to these decisions was a belief that individual freedom and agency is the path to long-term wellbeing, and that I could help make the case for good ideas that helped people live better lives.

Why should you care about any of this? Maybe you should not. There’s nothing remarkable about my experience. There are plenty of people who had it far worse for far longer, who have made far better of themselves. But there is something remarkable about a country that can afford a gimpy kid without a toilet the chance to study and learn, to hone and use skills, to fail, and then work harder, in order to build a better life for his family.

This brings me to the sensational headline. In recent days I’ve been told I hate poor people, or worse, that I want them to die, because I’ve voiced concerns about Medicaid expansion.

Obviously, this is absurd. I have experienced poverty and its consequences. I have seen first hand what subsistence looks like and have a permanent reminder every time I take a step with my left leg. I have eaten government cheese, and it’s not something you forget.

The debate over anti-poverty programs, like Medicaid, has never been between really good people who want to help the poor — not directly, mind you, but using other people’s money — and really bad people who want to see the poor suffer — many of these “bad people” quietly give more to charity than most of us could ever fathom.

That framing, well-meaning versus evil, is childish emotionalism. It’s manipulative. Worse still, it often leads to bad policies that line the pockets of favored industries while doing little to actually help poor people.

With the limited exception of some indifferent psychopaths, no one wants to see other people suffer.

The debate really is about what set of principles and ideas offers the greatest opportunity to escape generational poverty and live a life of meaning and contribution.

For generations, our country has surrendered the very real biblical call to help our neighbors to a vast bureaucracy of programs; programs which at best have helped to alleviate the discomfort of poverty and at worst have trapped people in it.

No state is a better example of government dependency than Mississippi. It’s not brought prosperity to our people.

Good intentions often do not yield good ideas or good results, which is one reason I’ve chosen to engage in the Medicaid expansion debate. What will we have actually accomplished if:

- The end result of Medicaid expansion is that we spend billions of dollars and health outcomes don’t meaningfully improve?

- If the most vulnerable people among us, children, pregnant moms, the elderly, and the disabled who are already on Medicaid, find themselves in competition for care with adults who refuse to work?

- If we force people off of private insurance and onto a welfare program that fewer doctors will accept, simultaneously distorting the payer mix that keeps the medical industry afloat?

- If hospitals don’t find long-term salvation from defects in their business model that have nothing to do with Medicaid?

- If people receive a benefit for not working, or not working full-time, and the end result is fewer people working to move up the economic ladder?

Another reason I’ve chosen to engage, and perhaps the more pressing one, is that no one else seemed willing to challenge the narrative that expansion was good and anyone who disagreed must not like the “working poor.” This may be effective political framing. After all, I’m responding to claims that I hate poor people and want them to die. But it’s a bad way to make policy. Opposition to ideas helps to hone ideas. Accepting narratives, with no deep reflection on risks, often results in bad policy that harms people, or the acceptance of “facts” that just aren’t so.

Take the work requirements discussion, as an example. Anyone who bothered looking would know that while President Trump did grant work requirements to 13 states, President Biden’s White House had successfully withdrawn all but one (Georgia) and had not granted any new work requirement waivers. To compound the problem, the D.C. Court of Appeals unanimously struck down work requirements in Arkansas, Kentucky and New Hampshire, and Georgia’s is the source of ongoing litigation. What’s even more telling, Mississippi has had a waiver request for work requirements on its existing Medicaid program since 2017 with no action.

All of that was only a Google search away, or a matter of consulting with actual healthcare experts, or even our own division of Medicaid. Finally, some other media sources, and even some proponents of expansion, are admitting work requirements probably aren’t possible. But I’ve been pointing it out for weeks.

And for all the talk of “working poor,” the primary beneficiaries of Medicaid expansion will be able-bodied people who refuse to work, or refuse to work full-time. How can I say that so definitively? Well, as we sit here today someone making minimum wage at a full-time job earns enough to be eligible for a 100% subsidized private plan on the ACA exchange without Medicaid expansion. And only 2 percent of Mississippi workers make minimum wage.

Knowing these things, it’s hard for me to imagine how full expansion will improve the likelihood of people joining the workforce. The Congressional Budget Office, for its part, has said expansion reduces workforce participation. Mississippi could very easily find itself in a situation with Medicaid expansion where we have one worker to every welfare recipient in the state. That’s not a sustainable path to prosperity. And it’s not just bad for taxpayers. It’s bad for the people who stay mired in poverty.

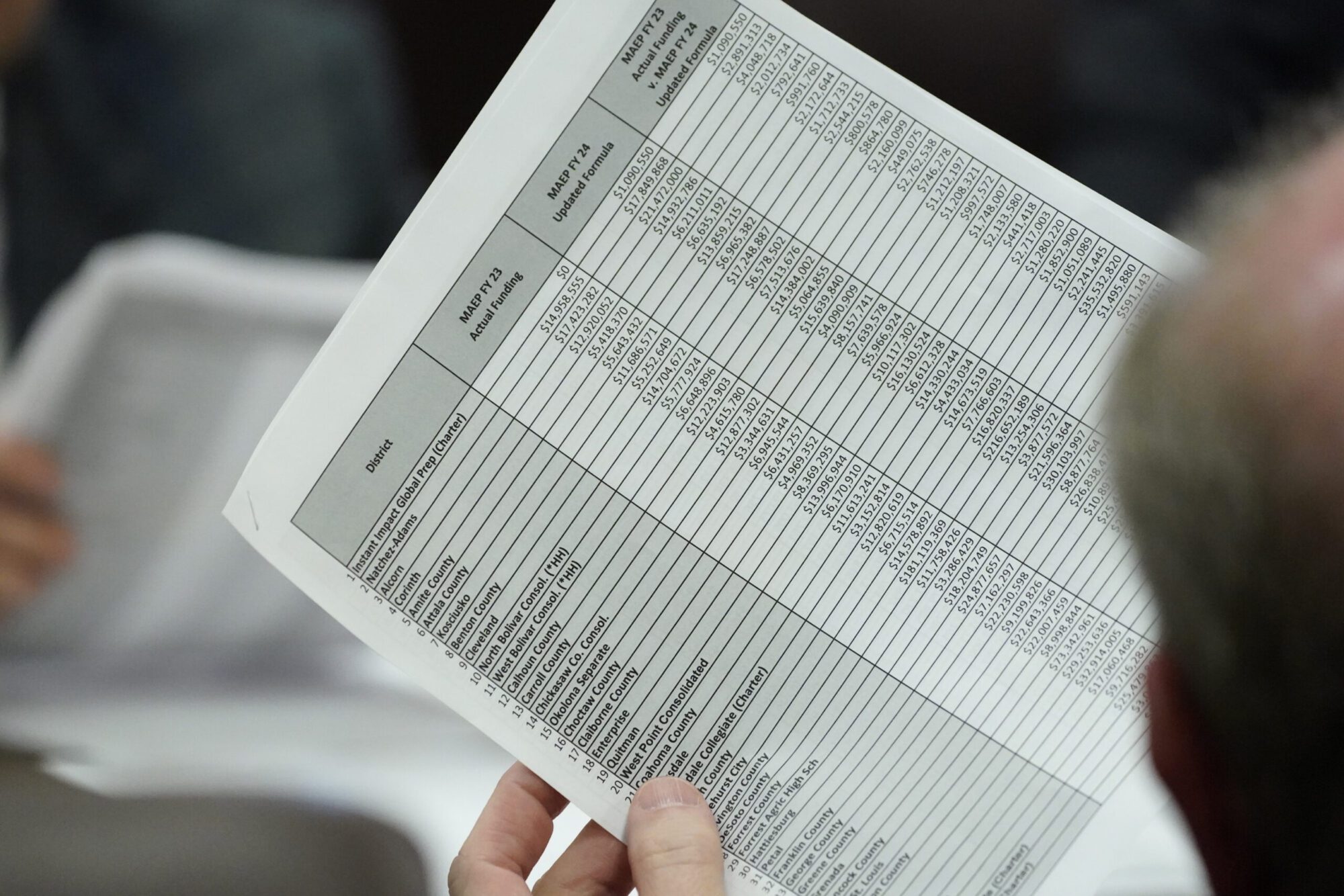

It has astounded me in recent days to see Medicaid expansion in Louisiana held up as a wild success. The state more than doubled the enrollment estimates for expansion and its Medicaid budget has almost doubled in just 8 years. It still has seen hospitals close and has the same percentage of hospitals deemed at risk as Mississippi.

When you do the math on jobs supposedly created by expansion there, each one comes at an annual — as in every year — taxpayer cost in the hundreds of thousands. Louisiana may be the only state in the country whose economy actually shrunk since it expanded in 2016. And despite testimony yesterday from the Mississippi Hospital Association, Louisiana’s labor force participation rate has not improved since expanding. In fact, it has declined at a slightly more rapid pace than Mississippi‘s. 1.9 percentage points versus 1.8 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Every economic impact statement that shows positivity from Medicaid expansion treats federal dollars as free and permanent. But federal dollars are neither free nor guaranteed. We are $34 trillion in debt as a nation, with unfunded liabilities for Social Security, Medicare, and pensions that are far larger. Our nation had a half trillion dollar deficit just in the first quarter of this year and interest on the debt is now over a trillion dollars — more than we spend on Medicare, Medicaid, our national defense or education. The Social Security and Medicare trust funds are due to be insolvent within a decade. Unserious people telling Americans what they want to hear, instead of what they need to hear, have brought our country to the brink.

This is the backdrop against which lawmakers are making decisions. “Good intentions” are writing bad checks that will bounce on our children and grandchildren for generations. Lastly, if I were to take every economic impact statement used to convince the Legislature to act, Mississippi would be sitting on a trillion dollar economy. Alas, we are not.

But set the money aside and look at health outcomes in a state like Louisiana. It continues to be ranked dead last in healthcare and health outcomes in the country. Put simply, that’s because most of our health problems in the South have nothing to do with whether there’s an insurance card in our wallet, one which may or may not be able to get us timely healthcare.

If the Legislature ultimately passes Medicaid expansion, I hope I am proven wrong. Legitimately. I hope we get healthy, that people use it as motivation to work, that hospitals suddenly are insulated from the fact that a business model built on in-patient care is no longer viable. But I’d be a lot more confident if there were signs risks and limitations had been deeply considered, even if ultimately rejected.

I don’t hate poor people. I want them to live full lives. For that to happen, there needs to be real debate of big policies that will have profound impact, good or bad, on our state.