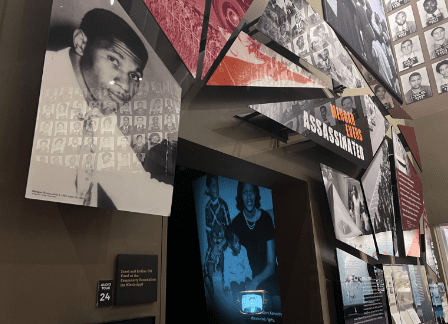

- The Rolling Fork and Stovall native went to Chicago and electrified the blues—and inspired the classic rock ‘n’ roll bands that followed.

If Hackney Diamonds ends up being the last album made by The Rolling Stones, its final two minutes and forty-one seconds would make an appropriate ending to the saga of the biggest rock ‘n’ roll band of all time.

The band’s improbably well received 2023 album—their 31st overall and a critical and commercial success—closes with a cover of the Muddy Waters tune that gave them a name in 1961.

“Rolling Stone Blues” scratches to life after the last notes of “Sweet Sounds of Heaven,” a seven-minute soul ballad featuring Lady Gaga, reach a crescendo and recede to silence. And that is where the studio polish ends.

Surfacing hazily as if through Delta dust, on “Rolling Stone Blues,” Keith Richards’s guitar crackles and buzzes like an old 78 rpm acetate. Mick Jagger’s honking harmonica doubles the melody between vocal lines, his lyrics borrowed from the century-old Delta staple “Catfish Blues” by way of Waters. It sounds like it could’ve been a field recording like the ones Alan Lomax made of Waters in 1941 and 1942, during his sharecropping days at Stovall Plantation.

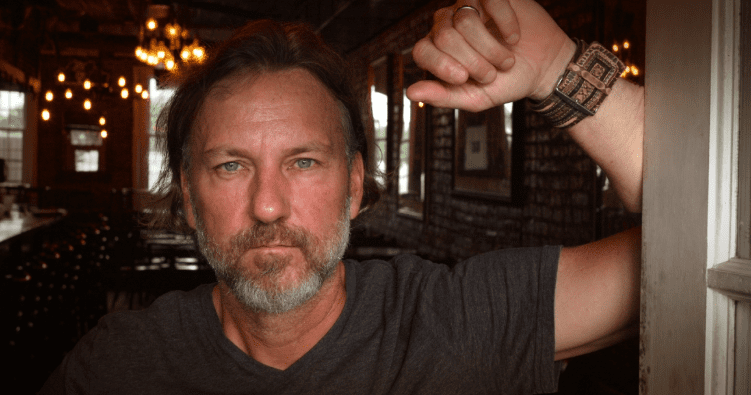

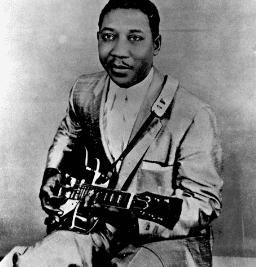

Waters was born McKinley Morganfield in Issaquena County in either 1913 or 1915, depending on the source, and grew up in Rolling Fork and at Stovall between Friars Point and Clarksdale. By the time he was a teenager, Waters was playing guitar and singing in juke joints at Stovall, and soon began traveling to other towns and farms in the Delta. Those first songs he recorded with Lomax gave him the confidence to pursue a career playing music, and in 1943 he left the farm behind for greener pastures up north.

After arriving in Chicago, Waters began performing for audiences at nightclubs on the city’s south side. But he couldn’t pick his acoustic guitar or sing loud enough to overcome the noisy crowds. Once he got an electric guitar and an amplifier, though, they heard him fine—and Waters suddenly had electrified the Delta blues, unwittingly beginning a new branch of the genre, dubbed Chicago blues.

During Waters’s early years in Chicago, he befriended another Mississippi ex-pat, Willie Dixon of Vicksburg, who joined him at Chess Records and began writing hits for Waters and Howlin’ Wolf (né Chester Arthur Burnett of White Station). While the two bluesmen jockeyed for Dixon’s best songs, Waters scored hits with Dixon-penned tunes like “Hoochie Coochie Man” and “I Just Want to Make Love to You.”

When the blues crossed the Atlantic, young British fans clamored for the imported records made by Waters, Wolf, Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. Brian Jones, who had teamed with Jagger and Richards, named their band The Rolling Stones after the Waters song and covered “I Just Want to Make Love to You” on their self-titled debut album in 1964.

The Beatles had already conquered America earlier that year, but the arrival of The Rolling Stones signaled the oncoming British Invasion, referring to the wave of English rock ‘n’ roll bands that had digested American blues and R&B, Anglicized it and then sold it back to them in the mid-sixties—bands such as The Kinks, The Animals, The Yardbirds and The Who.

Waters and other bluesmen enjoyed a renaissance during the decade, beginning with the success of Muddy Waters At Newport, a live recording of his 1960 performance at the Newport Folk Festival (no, Bob Dylan wasn’t the first artist to go electric at Newport—it was most likely Muddy in ‘60).

The Yardbirds evolved into the heavier Led Zeppelin, who went to the American blues songbook to adapt Dixon songs popularized by Waters. The band recorded “You Shook Me” for their debut album, Led Zeppelin, and “You Need Love,” which they morphed into “Whole Lotta Love,” for Led Zeppelin II. (The latter prompted a lawsuit in 1985 when Dixon’s family sued for songwriting royalties. The band settled and Dixon now has a credit on the song.)

From those touchstone rock ‘n’ roll bands, the family tree of artists whose music traces back to Waters broadens into a massive number of branches and leaves. Without Waters, you don’t get the Stones or Zeppelin, or any of the countless musicians they inspired. And while scores of blues musicians contributed to the sound and style of the genre and its many offshoots—R&B, soul, funk and rock, most notably—Waters is the direct link to the source for the popular music that followed.

Both Jagger and Richards are now 80 years old, and Waters, Dixon and the rest of the classic blues pioneers passed away long ago. Still, they both maintain Hackney Diamonds, which arrived 18 years after their previous original studio album, A Bigger Bang, won’t be their last recording. Jagger told The New York Times they’re already two-thirds done with the follow up, and Richards is optimistic about the band’s future in his own way.

“I’ve never even come close to thinking of wrapping up the Rolling Stones story,” Richards told Guitar Player in 2023. “It was just a cool way of wrapping up this album, and the story so far. We plan to keep working. I know we’re going to work next year. Making music is still quite exciting for me.”